A chronological journey from ancient times to the present day.

For tens of thousands of years, long before European arrival, the land we now call Ipswich was cared for and inhabited by the Jagera, Yuggera, and Ugarapul peoples. Archaeological evidence suggests continuous habitation for at least 40,000 years, making this one of the oldest continually occupied regions on Earth.

These First Nations people developed complex cultural systems, with seasonal migrations, sophisticated land management, and deep spiritual connections to the environment. The Bremer River was central to life, providing food, water, and trade routes. Sacred sites, story places, and Dreaming tracks are still known today, reminding us that Ipswich has always been more than just a settlement—it's a living cultural landscape.

Long before the first documented European landings in Australia, historical maps reveal that the wider world had knowledge of the Australian continent, or at least parts of it, far earlier than officially recognised. Some of the most intriguing evidence comes from early cartography, which points to a forgotten era of exploration and mapping in the southern hemisphere.

The Piri Reis map, created in 1513 by Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis, shows astonishingly accurate coastlines of parts of South America, Africa, and the northern Antarctic coast—despite Antarctica not being officially discovered until 1820. What makes this map extraordinary is that it seems to depict Antarctica’s coastline free from ice, as verified by modern geological and seismic scans which have mapped the bedrock beneath the continent's massive ice sheets.

Experts suggest that the source material for the Piri Reis map was drawn from much older charts, potentially dating back thousands of years to unknown civilizations who mapped Antarctica before it became covered in ice. Scientific studies of Antarctic ice cores suggest that the last time parts of Antarctica's coastline were ice-free was at least 6,000 years ago, with some estimates going back 12,000 years or more.

The first confirmed European presence on the Australian continent occurred in 1606, when Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon captained the vessel Duyfken ("Little Dove") into the waters of what is now known as Cape York Peninsula, in far northern Queensland.

At the time, the Dutch were a global maritime power. Operating through the Dutch East India Company (VOC), they were actively exploring and mapping unknown regions to expand trade routes, particularly between Europe, India, and the Spice Islands (modern Indonesia). It was during this era of aggressive exploration in the southern hemisphere that the Duyfken was dispatched on a voyage south of the Spice Islands, venturing into uncharted territory.

In early 1606, Janszoon and his crew sailed from the Dutch East Indies in search of new trade opportunities and potential lands of value. Heading into previously unrecorded waters, they crossed the Arafura Sea and skirted the coast of what is now Papua New Guinea, before turning south and making landfall on the western shores of Cape York Peninsula

This landing is historically significant, as it represents the first documented European contact with the Australian continent. Janszoon charted approximately 320 kilometres of Australia's coastline, mapping the Gulf of Carpentaria region and parts of northern Queensland. He referred to the land as part of "Nieu Zelandt", not yet recognising it as a separate and vast continent.

During the Duyfken's exploration along the coast, the crew made contact with local Aboriginal communities. Unfortunately, these interactions were hostile. Language barriers, cultural misunderstandings, and the sudden arrival of armed foreign sailors likely created fear and tension. According to Janszoon's accounts, some of his men were killed in clashes, leading him to abandon the voyage south and return to the Dutch strongholds in the East Indies.

These tragic encounters are among the first recorded meetings between Aboriginal Australians and Europeans, highlighting the earliest moments of what would become a long and often difficult relationship between Indigenous peoples and colonial powers.

Despite being the first to discover parts of Australia, the Dutch made no serious attempts to colonise the land. After further explorations by other Dutch navigators—such as Abel Tasman in the 1640s—the Dutch assessed the continent as barren and lacking in the spices, gold, or other valuable resources they were seeking. Without obvious commercial incentives, they focused their attention on the wealth of Indonesia and other parts of Asia, leaving the vast southern land they called "New Holland" largely ignored.

Consequently, inland Queensland, including areas like Ipswich, remained unknown and untouched by Europeans for nearly two more centuries.

Though the Dutch did not remain, the importance of the 1606 voyage cannot be overstated:

The Duyfken’s journey stands as the beginning of European awareness of the Australian continent, and although Ipswich itself was far from these initial contacts, this first point of entry into Queensland would, over time, ripple south as exploration expanded and the interior was eventually mapped and settled.

French explorers mapped parts of Australia’s coastline, contributing to early European knowledge.

Throughout the 1700s, as European maritime powers pushed further into the southern hemisphere, France emerged as a key player in exploring the uncharted coastlines of what was then known as Terra Australis. Building upon earlier Dutch voyages, the French sought to expand their own scientific knowledge and territorial ambitions by commissioning detailed expeditions to the mysterious southern lands.

One of the most significant of these voyages was led by Nicolas Baudin in 1800, though French interest in the Australian continent began decades earlier. French ships meticulously charted sections of the Australian coastline, with a strong focus on the southern and western shores. Their expeditions brought back extensive documentation of Australia’s unique flora, fauna, and geography, providing Europe with some of its first scientific records of the continent.

However, despite their meticulous surveys and scientific observations, the French, much like the Dutch before them, made no serious attempts to establish settlements. Their exploration remained largely coastal, and their interest in the Queensland region, including the land that would become Ipswich, was minimal. These inland areas, shielded by dense bushland and mountains, remained unexplored and untouched by Europeans. Yet, the work of the French helped lay the cartographic foundations that would later guide others.

The true turning point for sustained European involvement in eastern Australia—and the eventual founding of Ipswich—began with the arrival of Lieutenant James Cook on his historic voyage aboard HMS Endeavour in 1770. Unlike earlier Dutch and French expeditions, which largely focused on the northern and western coastlines, Cook's mission brought European eyes to the vast and largely uncharted east coast, opening the door to British claims over the land and the first steps towards colonisation.

Tasked by the British Admiralty with a scientific mission to observe the transit of Venus across the sun from Tahiti, Cook's orders included a secret second objective: to continue south in search of the fabled Terra Australis and chart any new lands encountered. After successfully completing his astronomical observations, Cook sailed west, eventually encountering the east coast of Australia near Point Hicks on April 19, 1770.

For the next several months, Cook and his crew meticulously mapped the coastline as they travelled northward, carefully documenting the natural harbours, inlets, islands, and coastal features of the land. This marked the first time that the eastern coastline of Australia had been accurately charted by Europeans, providing Britain with valuable knowledge about the continent’s potential.

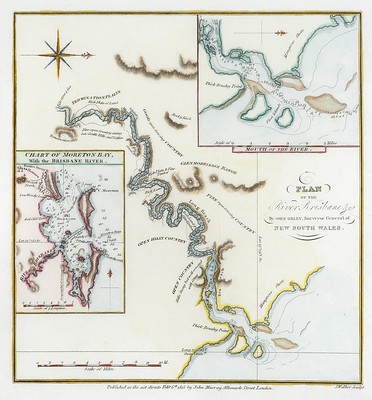

On May 15, 1770, Cook’s expedition sailed past Moreton Bay, the large coastal inlet that now borders Brisbane. Although Cook did not enter the bay or step ashore, his detailed observations noted the size and shape of the bay, its protective barrier islands, and the appearance of the land beyond the coast. Unknown to Cook, just 40 kilometres inland, the region that would one day become Ipswich lay beyond the distant hills—rich with resources, thriving with Aboriginal communities, and cradled by the Bremer River.

Cook's recordings of Moreton Bay and its surroundings were critical. His maps and journals sparked interest back in London, where Britain was looking for new lands to claim, settle, and exploit. The sheltered bay, navigable waters, and seemingly fertile lands beyond appeared ideal for future expansion, especially as Britain’s penal colonies struggled with overcrowding.

After continuing his journey north, Cook anchored at Possession Island in the Torres Strait on August 22, 1770, where he formally claimed the entirety of the east coast of Australia for King George III, naming it New South Wales. This act dramatically expanded the British Empire's reach, despite the fact that the land was already home to hundreds of sovereign Aboriginal nations who had cared for the continent for tens of thousands of years.

Cook’s declaration meant that everything from Point Hicks in the south to the tip of Cape York in the north—including the lands surrounding modern-day Ipswich—was, in the eyes of the British Crown, now part of its imperial holdings.

While Cook himself never ventured inland, his voyage directly set in motion the chain of events that led to the eventual colonisation of Queensland and the founding of Ipswich decades later. His detailed coastal charts were used by future explorers to navigate the region and opened the floodgates for British ambitions in the Pacific.

For the next 50 years, Moreton Bay remained largely uncolonised, but Cook’s reports ensured that it was firmly on Britain’s radar. By the early 1800s, British authorities, driven by the need for penal settlements and natural resources, began looking inland from Sydney and Brisbane. Cook's identification of Moreton Bay as a viable anchorage was the spark that led explorers to push beyond the coast into the interior—directly towards the Bremer River Valley and the lands that would become Ipswich.

While Cook never saw Ipswich or the rolling hills that surround it, his maps and reports were the first step toward the profound transformation of the region. In the years that followed, what had been a thriving Aboriginal cultural landscape for over 40,000 years would begin to feel the irreversible impact of European colonisation, with Ipswich at the heart of that story.

While the coastal regions of eastern Australia had been charted by James Cook in 1770, the vast interior—particularly the lands west of Moreton Bay—remained a mystery to Europeans for another 50 years. This changed in 1823, when British explorer John Oxley was sent to survey the region. His expedition would become a pivotal moment not only for Queensland but for the eventual establishment of Ipswich.

By the early 1820s, the British penal colony at Sydney was facing serious overcrowding, and there was an urgent need for additional sites to relocate convicts, particularly repeat offenders. The British government directed surveyors and explorers to identify suitable new settlement areas. Moreton Bay, with its large, sheltered harbour and proximity to fresh water sources, was identified as a promising candidate.

John Oxley, who was the Surveyor-General of New South Wales, was tasked with leading an expedition to assess the viability of establishing a penal settlement in Moreton Bay. In doing so, he not only explored the coastal areas but also ventured inland, becoming the first European to record observations of the rivers, floodplains, and fertile lands that would later support the growth of Ipswich.

Arriving at Moreton Bay in September 1823, Oxley and his party sailed up what was then an uncharted river. This river, of course, was the Brisbane River, though at that stage, its full course and tributaries were unknown to Europeans. It was during this exploration that Oxley encountered a remarkable stroke of luck: he met a shipwrecked Englishman named Thomas Pamphlett, who had been living with local Aboriginal people after being lost at sea.

Pamphlett and other castaways guided Oxley up the river, sharing their knowledge of the fertile country inland. This guidance was vital, as it allowed Oxley to travel further west than he otherwise might have ventured. As he moved along the river, Oxley reported the surrounding land as rich and well-watered, with abundant resources and good prospects for future settlement. These lands, lying just beyond the Moreton Bay coastline, included areas very near to what would soon become Ipswich.

During his expedition, Oxley identified the junction of the Bremer River and the Brisbane River. The Bremer River, flowing from the west, cuts through what is now Ipswich and was a crucial feature of the landscape. Oxley’s mapping of the Bremer River was the first formal European recognition of the river system that would later fuel Ipswich’s growth.

He noted in his reports that the lands surrounding the Bremer were “the finest I have seen in New South Wales”, a glowing endorsement that made the region highly attractive for future agricultural and industrial development. Oxley's exploration showed that the area west of Moreton Bay was not just inhabitable—it was potentially a powerhouse of resources, with fertile soils, fresh water, and, unbeknownst to Oxley at the time, vast coal seams.

Oxley's glowing accounts of the landscape directly influenced the British government's decision to establish the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement in 1824, which began as a small penal colony in what is now Brisbane. From there, exploration quickly pushed inland. Within just a couple of years of Oxley's report, the land that would become Ipswich was being surveyed and assessed for its natural resources.

Oxley didn’t personally establish a settlement at Ipswich, but his detailed descriptions and maps of the river systems made future development inevitable. By highlighting the strategic value of the Bremer River—both as a water source and a transport route—he unintentionally set Ipswich on a course to become Queensland’s first major inland industrial centre.

It's also important to acknowledge that while Oxley is credited with the "discovery" of these lands and rivers in colonial records, they were already well known, named, and carefully managed by the Jagera, Yuggera, and Ugarapul peoples. These Traditional Custodians had navigated, farmed, and lived along the Bremer River for thousands of years, with established communities, hunting grounds, and cultural sites throughout the region. Oxley’s arrival marked the beginning of profound disruption to these communities, whose way of life would soon be irrevocably altered by the waves of settlers that followed his positive reports.

Oxley's 1823 exploration is a clear turning point in the history of Ipswich:

This moment, more than any before it, opened the door to the creation of Ipswich as we know it—a vital inland centre that would, within just a few decades, become a hub of industry, mining, and culture in the heart of Queensland.

Following the positive reports from John Oxley just a few years earlier, British interest in the lands west of Moreton Bay intensified. In 1826, this interest led to one of the most significant exploratory missions in the region’s early colonial history, led by Captain Patrick Logan, commandant of the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement.

Captain Patrick Logan was an officer of the 57th Regiment and the head of the harsh Moreton Bay Penal Settlement from 1826 to 1830. Known for his strict discipline and rigorous use of convict labour, Logan was also an ambitious and skilled explorer. He sought out new opportunities for agricultural expansion, resource extraction, and ways to support the growing demands of the penal colony.

In search of farmland, timber, and other exploitable resources to sustain the Moreton Bay settlement, Logan led a series of expeditions into the interior, pushing beyond the relatively well-known coastal strip into what was still, to Europeans, an uncharted inland region. Following the course of the Brisbane River, Logan and his team travelled westward, eventually encountering the Bremer River.

It was along the banks of the Bremer, near what is now Ipswich, that Logan made one of Queensland's most significant early discoveries: exposed coal seams. These seams were clearly visible in the riverbanks and surrounding hills, and their potential was immediately obvious. Coal was essential for fuelling the growing industrial ambitions of the colony, from blacksmithing to heating and eventually powering steam engines.

Logan’s documentation of these coal deposits marks Queensland’s first officially recorded coal discovery. While Aboriginal people of the region would have long been aware of the black stone’s presence, it was Logan's identification that triggered official interest and exploitation.

This discovery instantly elevated the importance of the Ipswich region. Coal was a resource of enormous value—fuel for industry, transportation, and export. Logan's reports back to the colonial authorities in Sydney described not only the richness of the coal seams but also the quality of the surrounding land for settlement and agriculture.

Logan’s findings positioned the area as a key future site for development, both for its strategic inland location and its rich natural resources. These reports set the foundation for formal European occupation and commercial exploitation of the region.

In response to Logan's discoveries and his glowing reports of the land’s potential, colonial authorities moved quickly. By 1827, an official outpost was established along the Bremer River. This settlement was named Limestone Station, after the abundant limestone deposits found in the hills surrounding the river.

Limestone was another critical resource for the early colony. It was used in construction—particularly in making lime mortar, essential for building durable structures in the fledgling penal settlement of Moreton Bay. The demand for high-quality building materials was growing as the colony expanded, and the limestone deposits near the Bremer River provided a readily accessible and plentiful supply.

Convict labourers stationed at Limestone Station were tasked with quarrying the limestone and preparing it for transport back to Brisbane via the river. Boats and barges were loaded with limestone and floated down the Bremer River, into the Brisbane River, and onward to the coastal settlement.

What began as a remote quarrying outpost soon grew. Limestone Station was strategically located—not only close to valuable coal and limestone but also at the convergence of important waterways. The Bremer River provided a natural transportation route, and the surrounding land was fertile and suitable for grazing and agriculture.

As demand for resources increased, so too did the settlement’s importance. Buildings were constructed to house the convict workers, store supplies, and manage the growing quarry operations. Over time, more free settlers arrived, seeking to farm the fertile plains and exploit the rich resources Logan had first identified.

By the late 1830s, Limestone Station was evolving from a simple resource camp into a permanent township, driven by trade, agriculture, and mining. Its name, however, would not last much longer. In 1843, the settlement was officially renamed Ipswich, after the town of Ipswich, England, marking the next chapter in its transformation from a penal outpost into one of Queensland’s first inland cities.

The exploration of Captain Patrick Logan and the establishment of Limestone Station represent a turning point in Queensland’s colonial development:

But this period also marks the beginning of profound disruption to the Jagera, Yuggera, and Ugarapul peoples. The establishment of Limestone Station brought deforestation, land clearing, and violent displacement, as European settlers claimed land that had been sustainably managed for thousands of years.

From this point forward, Ipswich’s story became deeply entwined with both progress and conflict, resource wealth and cultural loss, shaping the city’s complex legacy that continues into the present day.

By the early 1840s, the humble convict outpost known as Limestone Station had begun transforming into something far greater. Fueled by the region's abundant natural resources—especially limestone, coal, and timber—the settlement quickly grew into a vital inland hub. What had begun as a remote supply camp for the penal colony at Moreton Bay was evolving into a bustling centre of commerce and industry, servicing both the coastal settlement of Brisbane and the increasingly populated agricultural lands stretching further west into Queensland’s interior.

Strategically located on the Bremer River, Limestone Station was ideally positioned to serve as a transfer point. Limestone, coal, and timber extracted from the surrounding hills and forests were loaded onto boats and transported downriver to Brisbane. These resources supported the colony's growing construction needs, fuelled steam engines, and provided materials for expanding farms and settlements.

In addition to its booming quarry and mining operations, the area surrounding Limestone Station attracted early pastoralists. The land's fertile river flats and open woodlands were suitable for grazing cattle and growing crops, adding an agricultural dimension to the area's economy.

However, with its location on the banks of the Bremer River, the growing settlement faced a serious natural threat that would haunt its history: flooding.

In January 1841, Ipswich experienced its first major recorded flood. Heavy summer rains caused the river to swell rapidly, inundating the small but developing settlement. The flood destroyed early infrastructure, washed away supplies, and disrupted the critical transport of limestone and other goods downriver. The event exposed the vulnerability of the settlement's low-lying areas and signalled a recurring pattern that would plague Ipswich throughout its history.

This flood was a sobering moment for the early residents. It forced colonial authorities and settlers to reconsider how and where they built their infrastructure, influencing future urban planning and encouraging the construction of more durable buildings and river management strategies. Despite the devastation, the community recovered, and the flood did little to slow the town’s upward trajectory.

By 1843, just two years after the flood, the settlement's growth was undeniable. As more free settlers arrived, and the area's industrial importance solidified, the time came to give the community a formal name worthy of its status.

In that year, Limestone Station was officially renamed Ipswich, after the historic town of Ipswich, England. The choice of name reflected not only the British heritage of the settlers but also symbolised the colony's ambitions to build lasting cities that would mirror the established towns of the United Kingdom.

This renaming marked Ipswich’s transition from a penal resource outpost into an established township, setting the stage for further industrialisation and population growth. Over the next two decades, Ipswich developed rapidly, attracting tradespeople, merchants, and entrepreneurs eager to tap into the region's rich resources and growing market.

Throughout the 1850s, Ipswich experienced a period of remarkable growth and transformation. What had begun just a few decades earlier as a modest convict outpost was now evolving into one of the most significant inland centres in the colony of Queensland. Several key developments during this decade propelled Ipswich from a mining village into a thriving regional powerhouse.

By the mid-1850s:

By the end of the decade, Ipswich had outgrown its early colonial identity. It was now a dynamic commercial centre with real political influence and ambitions far beyond its origins.

As Ipswich prospered, so too did its cultural and social institutions. Among the earliest and most influential was Freemasonry, which established a presence in Ipswich during this same period of rapid growth. The first Masonic lodge in Ipswich was Lodge of St. George, consecrated in 1859, making it one of the earliest lodges in Queensland outside Brisbane. The man credited with founding Freemasonry in Ipswich was Captain George Thorn, an influential figure who had emigrated from England and became deeply involved in the political, commercial, and social life of the young colony.

Who Was Captain George Thorn?

Under Thorn’s guidance and influence, the Lodge of St. George became a centre of civic activity. Freemasonry provided a network through which local leaders could collaborate on public works, social welfare projects, and charitable efforts—many of which contributed directly to the improvement of Ipswich during its formative years.

The founding of Freemasonry in Ipswich coincided with its broader rise across colonial Australia. Lodges were not only fraternal organisations but also places where influential figures in government, business, and industry could meet to coordinate civic projects and share knowledge. Freemasonry played a quiet but vital role in shaping the responsible governance and community-oriented spirit of early Ipswich.

By 1860, the case for Ipswich's importance was impossible to ignore. The township’s economic success, resource wealth, and growing population led to it being formally declared a municipality. This designation allowed Ipswich to establish its own municipal council, giving residents control over local governance, public services, infrastructure, and lawmaking.

By this time, Ipswich was among the largest and wealthiest settlements in the newly established colony of Queensland. Such was its prominence that Ipswich was seriously considered as a candidate for Queensland’s capital. Advocates pointed to its inland location, resource wealth, and central role in trade and industry, arguing that Ipswich was better positioned to lead the colony.

However, in the end, Brisbane was selected due to its larger population and more direct access to maritime trade routes. Despite this, Ipswich continued to dominate Queensland’s industrial and agricultural output.

During this era, Ipswich earned the nickname “The Workshop of Queensland,” a title that reflected its manufacturing capabilities, heavy industry, and resource extraction. From railways and coal to timber and agriculture, Ipswich provided much of the material and economic foundation upon which early Queensland was built.

Freemasonry, led by figures like Captain George Thorn, played an essential role in this era of progress, as many prominent Masons contributed to the town's development through leadership roles, philanthropy, and public service.

By the 1860s, Ipswich had firmly established itself as a leading industrial centre in Queensland, with coal mining, limestone quarrying, and agriculture driving its economy. However, in 1863, the region experienced a brief but notable period of gold fever with the discovery of gold at Peak Crossing, a small rural locality located approximately 20 kilometres south of Ipswich.

In 1863, reports surfaced of gold being found in the hills and creek beds around Peak Crossing. Although the deposits were relatively small, word of the discovery quickly spread through the colony. The global gold rushes of the 1850s—particularly in Victoria and New South Wales—had already proven how transformative such discoveries could be, bringing massive waves of migrants, investment, and infrastructure. As a result, even modest gold finds sparked excitement.

Local prospectors and fortune-seekers descended on Peak Crossing, hoping to strike it rich. Makeshift camps sprang up almost overnight as miners staked their claims and began panning the creeks and digging shallow shafts. For a brief time, Peak Crossing hummed with the sounds of pickaxes and gold pans as the promise of wealth drew people from nearby towns and settlements.

While Ipswich itself did not sit on a goldfield, its position as the nearest major township meant it directly benefited from the discovery in several ways:

While the Peak Crossing gold rush was modest in comparison to the major southern goldfields, it nonetheless injected a fresh burst of economic activity into the region and added yet another layer to Ipswich's growing industrial and commercial influence.

Unlike the Victorian goldfields, where gold was found in vast quantities and extracted through deep-shaft mining operations that lasted decades, the gold at Peak Crossing was relatively shallow and quickly exhausted. Within a few years, most prospectors had moved on to richer fields elsewhere in Queensland, such as Gympie (discovered in 1867) and Charters Towers.

Peak Crossing settled back into the quiet agricultural community it remains today, but its short-lived gold rush is still remembered as a fascinating chapter in Ipswich’s broader history.

The excitement generated by the gold discovery came during a decade of rapid development for Ipswich. By the time of the Peak Crossing gold rush, Ipswich was already transitioning from a frontier settlement into a well-established regional city. The brief influx of prospectors and trade further reinforced Ipswich’s role as the service and commercial centre for the surrounding rural districts.

Perhaps more importantly, the events of 1863 highlighted Ipswich’s strategic importance:

While gold may not have defined Ipswich's destiny in the way coal and industry did, the discovery at Peak Crossing is a reminder of the diversity of natural wealth in the area and Ipswich's ability to support and capitalise on such opportunities.

With its population growing and its industries expanding, Ipswich was on the cusp of its next major leap forward. Just two years later, in 1865, another transformative event would secure Ipswich's place as Queensland’s industrial heart: the opening of the North Ipswich Railway Workshops.

By 1863, when gold was discovered at Peak Crossing, Freemasonry in Ipswich was already well established and thriving. The Lodge of St. George, consecrated in 1859 under the leadership of Captain George Thorn, had become a cornerstone of Ipswich’s social, charitable, and civic life.

As gold fever briefly swept through the region:

Freemasons were among the prominent business owners, merchants, and civic leaders who helped organise and supply the sudden influx of prospectors. Many of the local suppliers of equipment, provisions, and accommodation were operated by members of the lodge, who ensured the region could meet the demands of miners passing through Ipswich on their way to the goldfields. The lodge provided a sense of order, stability, and fraternity during this time of rapid, unpredictable economic activity, as transient populations and opportunistic speculators moved through the area. Masonic values of community service and charity likely influenced local efforts to assist both established residents and itinerant miners, particularly as some failed to find riches and required support before moving on.

During periods of economic excitement, such as the Peak Crossing gold rush, Ipswich’s standing as a commercial hub was reinforced not only by its industries and infrastructure but also by its cohesive leadership network, of which the Freemasons were a central part. Through regular meetings and community engagement, the Freemasons of Ipswich helped foster:

Business partnerships that expanded trade. Civic improvements, including support for roads, public buildings, and social welfare projects. Long-term planning for Ipswich’s future, ensuring that temporary booms, like the gold rush, contributed to sustained prosperity.

As such, while the gold at Peak Crossing may have been limited, the infrastructure, commerce, and leadership—shaped in part by Freemasonry—ensured that Ipswich remained the lasting beneficiary of any temporary wealth passing through the region.

By the mid-1860s, Ipswich had firmly established itself as one of Queensland’s most important centres of industry and trade. Its strategic inland location, abundant natural resources, and rapidly growing population made it the ideal site to support the young colony’s ambitions for an expansive rail network to connect the coast with Queensland’s interior. These ambitions came to life in 1865 with the opening of the North Ipswich Railway Workshops—an event that cemented Ipswich as the beating industrial heart of Queensland.

As settlement spread inland, there was an increasing need for reliable and efficient transportation of essential goods such as coal, timber, wool, and agricultural produce to and from the coast. Previously, the Moreton Bay region had relied heavily on river transport and rough bush tracks, which were no longer sufficient to support the demands of a growing colony. The solution lay in the development of a railway network, and Ipswich, as the colony’s key inland centre, was chosen as the hub of Queensland’s very first railway line. This line opened in 1865, running from Ipswich to Grandchester, marking the beginning of what would become Queensland’s vast and vital rail system—with Ipswich leading the way.

To manage and oversee the complex operation of this pioneering railway project, the Queensland Government sought experienced leadership from abroad. They recruited John Kennedy Donald, a highly regarded civil engineer and Freemason from St. Mark’s Lodge No. 102 in Glasgow, Scotland. Donald brought with him invaluable knowledge and technical expertise, drawn from his extensive work in managing railway infrastructure across the British Isles.

In 1864, Donald was appointed Queensland’s first Traffic Manager, charged with overseeing the railway’s day-to-day operations between Ipswich and Grandchester. Under his leadership, the new railway system was meticulously organised and operated with the precision required to ensure its success in a colony that depended on reliable transport for economic survival. Donald’s work was critical not only in setting up Queensland’s rail operations but also in establishing Ipswich as the state’s primary inland transport hub.

Beyond his contributions to Queensland Rail, John Kennedy Donald made a lasting impact on the Ipswich community through his role in the establishment of Freemasonry in the region. Recognising the growing number of Scottish migrants and railway workers living in Ipswich, Donald helped found Caledonian Lodge No. 14 in 1866, under the Scottish Constitution, and served as its first Worshipful Master. Through his leadership, the lodge provided vital social cohesion, charitable support, and moral guidance to the community during a time of rapid industrial growth.

As Ipswich transitioned into a major industrial and railway town, Freemasonry became deeply woven into the fabric of its leadership and workforce. Many of the senior railway engineers, supervisors, and skilled tradesmen were active Freemasons, fostering strong bonds between industry, government, and civic society. The shared principles of brotherhood, craftsmanship, and community service mirrored the ethos of the North Ipswich Railway Workshops themselves, which trained generations of workers through rigorous apprenticeship systems. These Masonic networks were instrumental in providing ongoing support within the community

John Kennedy Donald's dual legacy as both a railway leader and a Masonic pioneer helped guide Ipswich through one of its most critical periods of growth, ensuring that the boom of industry was matched by strong social infrastructure and a sense of shared purpose.

The Great Flood of 1893 stands as one of the most catastrophic natural disasters in Ipswich’s history, and one of the defining events of the late 19th century for the entire Brisbane River and Bremer River catchment areas. Long remembered in local lore and recorded history, the flood revealed both the devastating power of nature and the extraordinary resilience of the Ipswich community.

In early February 1893, a series of powerful cyclones and prolonged, torrential rainfalls struck southeast Queensland. Over several days, extraordinary volumes of water poured into the already saturated catchments of the Brisbane River and its major tributary, the Bremer River, which runs directly through Ipswich.

With nowhere else for the water to go, the Bremer River rapidly rose to unprecedented levels. On 5 February 1893, the river peaked at an estimated 24 metres (79 feet) at Ipswich, engulfing large sections of the town and wiping out everything in its path. This flood remains the highest on record for the region.

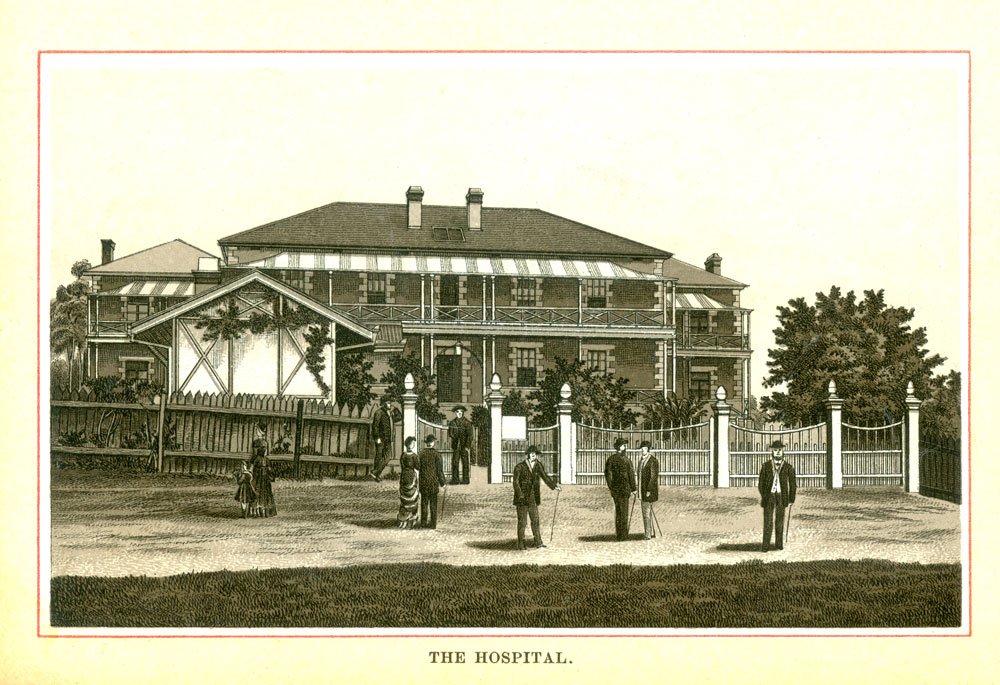

As floodwaters receded, they left behind a trail of mud, debris, and destruction. Disease became a serious concern in the weeks that followed, with stagnant water and ruined food supplies threatening public health.

Despite the overwhelming scale of the disaster, the people of Ipswich rallied with remarkable determination. Neighbours helped neighbours, and community groups, including Freemasons, churches, and civic organisations, mobilised to provide aid. Lodges like Lodge of St. George and Caledonian Lodge, already strong pillars of the local community, contributed to relief efforts by organising donations, supporting displaced families, and helping rebuild essential services.

The Freemasons, in particular, extended financial assistance, food, and shelter to affected members and the wider community, upholding their values of charity and brotherhood during the town's darkest days. With so many railway workers and tradesmen among their ranks, the Masonic lodges played a vital role in coordinating the skilled labour needed to restore Ipswich’s critical infrastructure.

The recovery process took years. Entire streets had to be reconstructed, new bridges designed to withstand future floods were built, and flood mitigation strategies were proposed. The 1893 flood left scars on the physical landscape of Ipswich, but it also reinforced the town’s communal identity as a resilient and determined place that could withstand and overcome hardship.

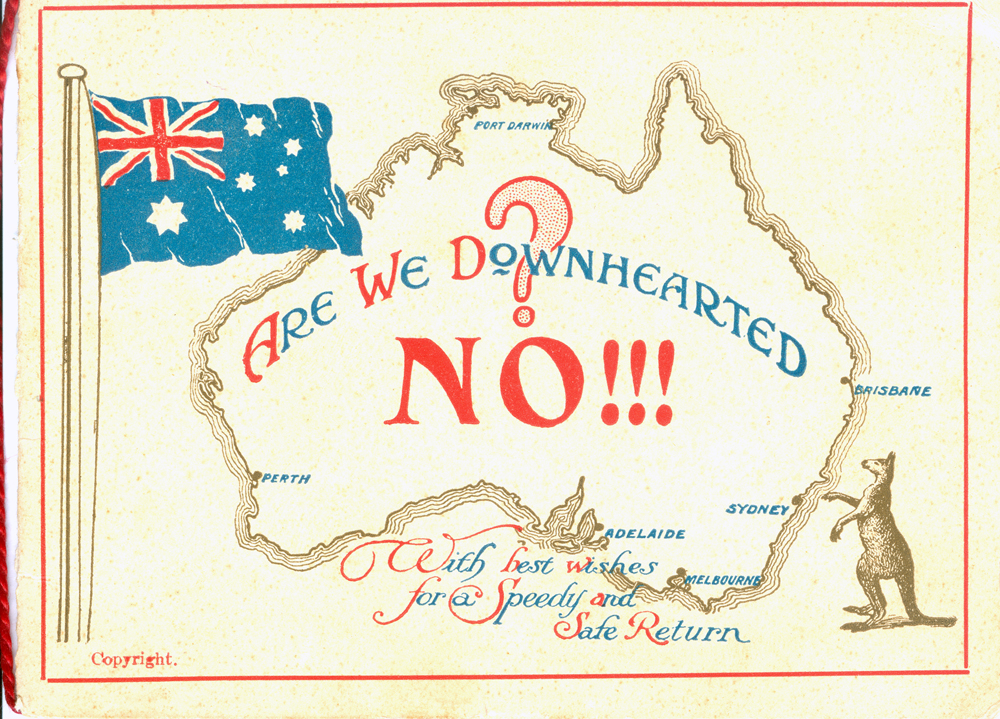

The period from 1914 to 1945 was one of profound challenge and transformation for Ipswich. Spanning both World War I and World War II, these decades tested the city’s people, industries, and institutions. Yet, through sacrifice and innovation, Ipswich not only endured but further cemented its reputation as Queensland's industrial heart and a key contributor to Australia's war efforts.

When war broke out in August 1914, Ipswich responded swiftly and patriotically. Hundreds of local men enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), joining battalions that would serve in some of the most brutal theatres of the war, including Gallipoli, the Western Front, and the Middle East. The losses were deeply felt across the community, as sons, fathers, and brothers left Ipswich’s factories, farms, and coal mines to serve overseas, with many never returning.

On the home front, Ipswich’s industries played a crucial role in supporting the war effort:

Freemasonry in Ipswich also played an active role during this period. Lodges such as St. George, Caledonian, and others provided vital assistance to the families of servicemen, supported war charities, and upheld morale within the community. With many Freemasons among those who served, the lodges became important spaces of remembrance, solidarity, and charity throughout the war years and after.

The years following World War I were a period of both recovery and reflection. Ipswich, like much of Australia, grieved the loss of a generation. Memorials were erected, including the Ipswich War Memorial in Limestone Park, to honour the fallen.

Industrially, Ipswich remained strong. The post-war years saw continued growth in the railway workshops, and coal mining remained robust. However, the Great Depression of the 1930s hit the city hard, causing widespread unemployment and hardship. Yet, through strong communal ties, support from civic groups—including the Freemasons—and sheer determination, Ipswich weathered the economic storm.

Just as Ipswich was finding stability, World War II erupted. Once again, the people of Ipswich answered the call to service. More than 3,000 men and women from the region enlisted, serving in campaigns across the Pacific, Europe, and North Africa.

Ipswich’s strategic importance increased dramatically during the Second World War:

During both world wars, Ipswich’s residents demonstrated extraordinary community spirit. Women stepped into roles left vacant by enlisted men, working in factories, shops, farms, and even within the railway workshops. Local organisations organised fundraisers, blood drives, and care packages, ensuring that soldiers abroad felt the support of home.

Freemasonry again played a key part during this era. With many lodge members serving overseas, the lodges became centres of support for families, offering financial assistance, counselling, and community events to maintain morale. Memorial services were held regularly, and lodges contributed generously to war charities.

By 1945, as the world emerged from the shadow of war, Ipswich stood as a city defined by resilience, sacrifice, and industry. The wars had tested the community’s strength but had also brought growth, innovation, and a new sense of identity. The railway workshops and coal mines had proven their strategic value, and the skills of Ipswich’s workforce were recognised across the country.

The impact of the wars endured long after the final shots were fired. Returning veterans shaped the post-war community, leading civic groups, businesses, and councils. War memorials and Anzac ceremonies became permanent fixtures in Ipswich life, ensuring that the sacrifices of those who served would never be forgotten.

Through it all, Ipswich's core industries—rail, coal, and agriculture—remained strong, supported by a community whose shared experiences of hardship and triumph had only deepened their commitment to building a better future.

The decades following World War II marked a period of significant change for Ipswich. After nearly a century as Queensland’s industrial engine, built on the back of coal mining, railway manufacturing, and heavy industry, global economic shifts and the emergence of new technologies led to the gradual decline of these traditional pillars of the local economy. The post-war years became a time of both challenge and reinvention for the people of Ipswich.

Coal mining had been the backbone of Ipswich since the mid-1800s. By the early 20th century, Ipswich’s mines were producing thousands of tonnes of coal annually, fueling not only local industry but also powering Queensland’s expanding rail network and providing export income.

However, by the 1950s, cracks began to appear in the industry:

By the 1960s and 1970s, mine closures became common, and the once-bustling coalfields that had sustained entire communities around Ipswich fell silent. The economic and social impact was profound. Families who had mined the same seams for generations found themselves facing unemployment, and once-thriving mining towns and suburbs entered periods of decline.

The workshops, once among Queensland’s largest employers, gradually downsized operations. By the 1980s, much of the site had ceased major production, marking the end of an era that had defined Ipswich's identity for over 100 years.

Just over 80 years after the catastrophic flood of 1893, Ipswich once again found itself at the mercy of the Bremer River. On January 26, 1974—Australia Day—the city experienced one of its most devastating natural disasters of the modern era. The 1974 flood remains etched in Ipswich’s collective memory as a moment of overwhelming loss, resilience, and community spirit.

In the weeks leading up to Australia Day 1974, Queensland was battered by a series of intense tropical storms. Heavy rainfall saturated the ground, and catchments across the southeast were pushed to their limits. When Tropical Cyclone Wanda moved into the region, it delivered unprecedented rainfall directly into the already swollen Brisbane and Bremer River systems

As the floodwaters surged, the Bremer River rose rapidly. By the time it peaked, the river had reached a height of approximately 20 metres at Ipswich—submerging large parts of the city and its surrounding suburbs.

Entire neighbourhoods, particularly low-lying areas near the river such as East Ipswich, West Ipswich, and Booval, were submerged. Families who had lived in the same homes for generations lost everything overnight.

By the 1990s, Ipswich was a city in transition. Having endured the slow decline of its traditional industries—particularly coal mining and rail manufacturing—Ipswich stood at a crossroads. With its industrial era fading into history, the city shifted focus towards renewal, diversification, and modernisation, setting the stage for the vibrant, growing regional centre it would become in the decades that followed.

The downturn of Ipswich’s heavy industries in the 1960s through 1980s had left parts of the city struggling with unemployment and economic stagnation. Entire suburbs once built around coal mines and railway workshops were faced with uncertainty as generations-old sources of work disappeared. But the 1990s brought fresh opportunities as Ipswich began to reinvent itself.

One of the key pillars of Ipswich’s renewal was its investment in education. Recognising the need to provide new skills and pathways for its younger population, the city welcomed:

For much of the 20th century, Ipswich’s population growth had been steady but modest. However, during the 1990s, the city began to experience a population boom. Affordable housing, improved services, and its strategic position within commuting distance of Brisbane made Ipswich a desirable destination for new residents.

From its early days as a limestone outpost and industrial powerhouse, Ipswich has undergone a remarkable transformation. Today, the city stands as one of Queensland’s fastest-growing regions, with a thriving population now exceeding 240,000 and continuing to rise rapidly. Once defined by coal mines and railway workshops, modern Ipswich has evolved into a dynamic, diverse, and forward-thinking city that embraces both its rich heritage and its ambitious future.

As southeast Queensland’s population surged in the early 21st century, Ipswich found itself at the centre of unprecedented expansion. Offering affordable housing, strong infrastructure, and an enviable lifestyle within commuting distance of Brisbane, the city became a magnet for families, professionals, and businesses seeking space and opportunity.

Master-planned communities such as Springfield and Ripley Valley reshaped the landscape. These vast, purpose-built suburbs introduced thousands of new homes, schools, parks, and shopping centres, designed to create self-contained communities with modern amenities and strong local economies.

One of the cornerstones of Ipswich's modern economy is RAAF Base Amberley, located just west of the city. Now the largest air force base in Australia

Amberley’s presence has been transformative for Ipswich, contributing billions of dollars to the regional economy, supporting local businesses, and attracting skilled workers and their families to the area.